7 Learnings about Compute Strategy for Middle Powers

Access to compute is a key ingredient of AI sovereignty. Middle powers can only catch up if the political will matches the stakes.

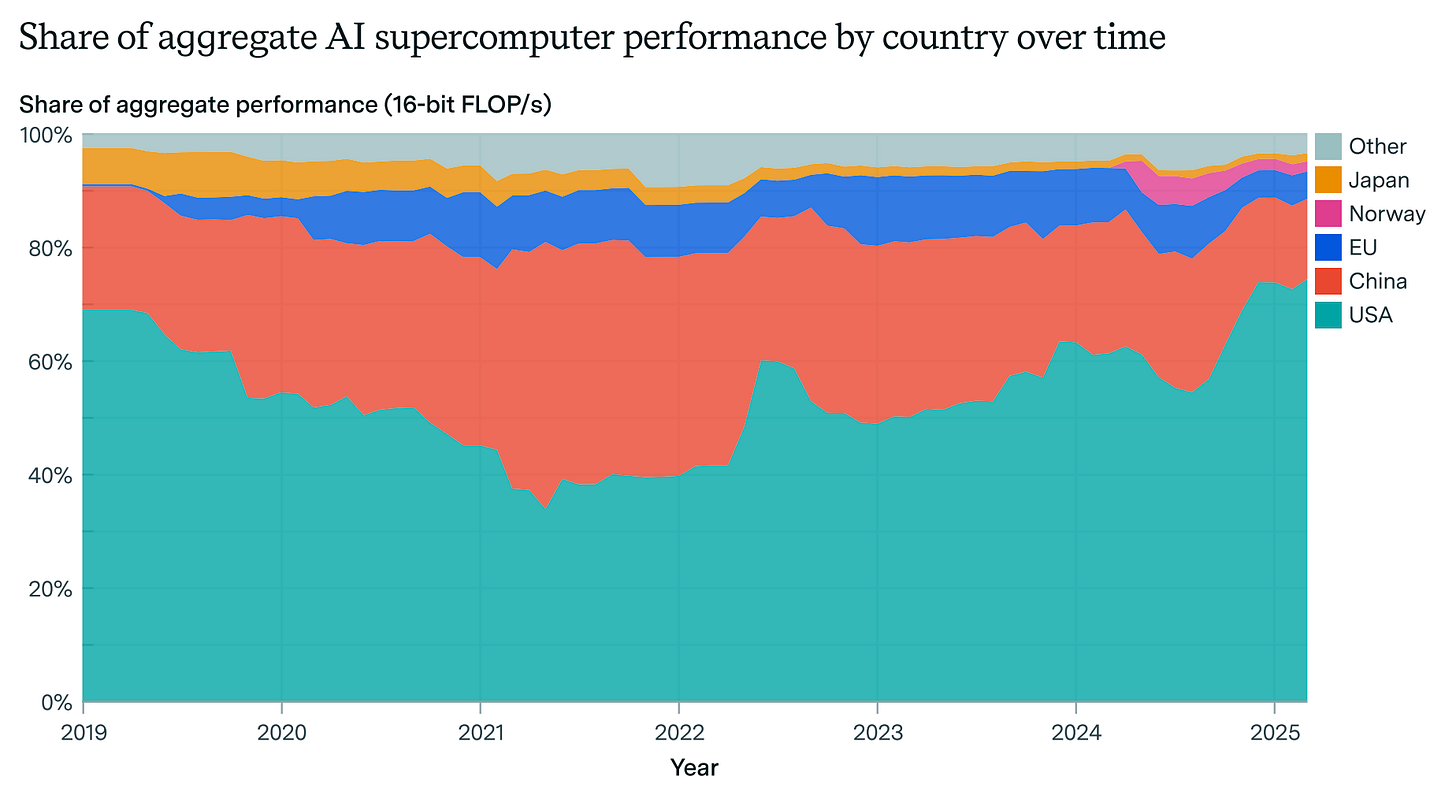

Middle powers are in a tight spot. They are so far behind the US and China in the global AI race that catching up will be very difficult. Yet they have to catch up – if not to the frontier, then at least to a sufficiently strong position –, if AI turns out as strategically important as many experts predict.

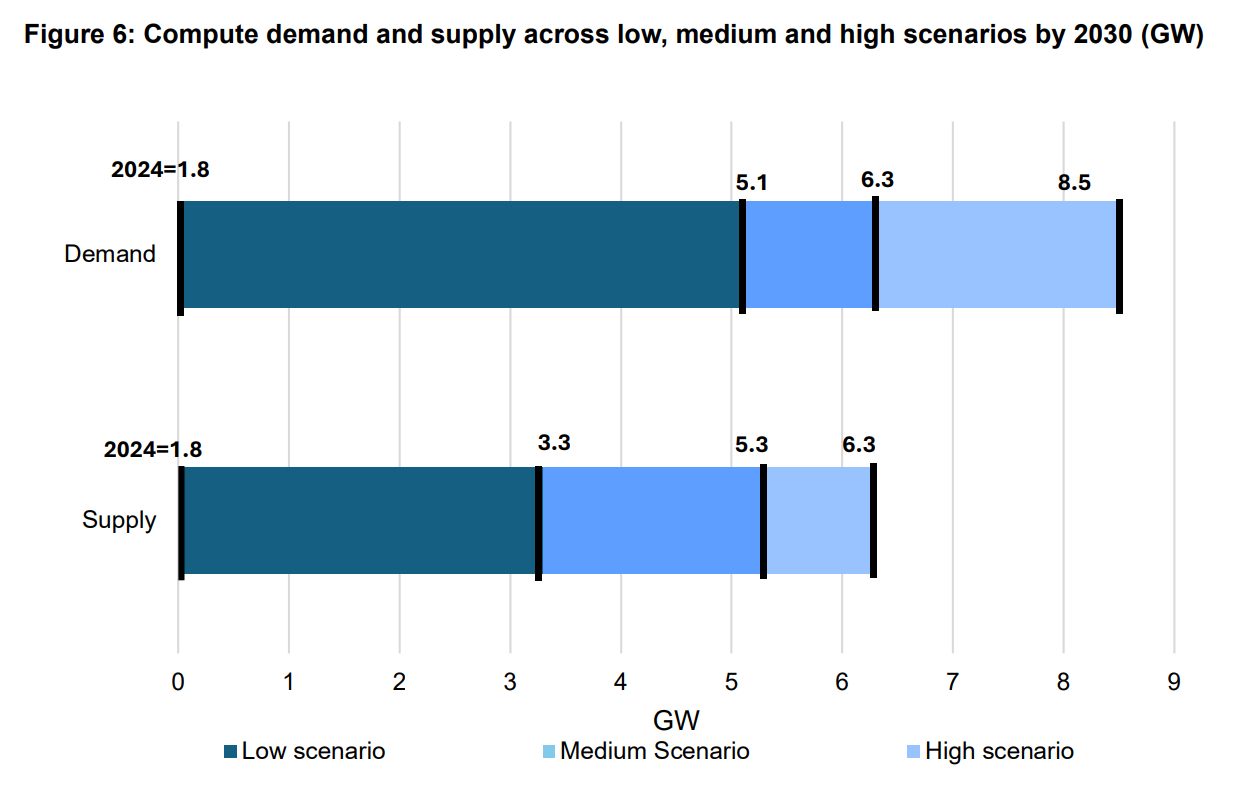

A key ingredient to AI competitiveness is compute: the computational resources necessary to train and deploy (‘inference’) AI models. Together with Prof. Monika Schnitzer (German Council of Economic Experts) and Daniel Privitera (KIRA Center), I have written a compute roadmap for Germany. (Views in this post are exclusively my own, however.) We found that Germany’s share of global AI compute is about to shrink dramatically and outline three possible strategies for addressing the resulting compute gap, requiring between 0,8 and 6 GW of AI data center capacity by the end of 2028.

I believe that our main findings generalize beyond a German context. Middle powers all confront the same challenges, related to technological and strategic uncertainty, sovereignty constraints, GPU access and multilateralism, among others. In this post, I share 7 learnings on compute strategy that I think will be useful for people faced with similar challenges elsewhere.

1) Projecting future compute demand is especially hard for middle powers.

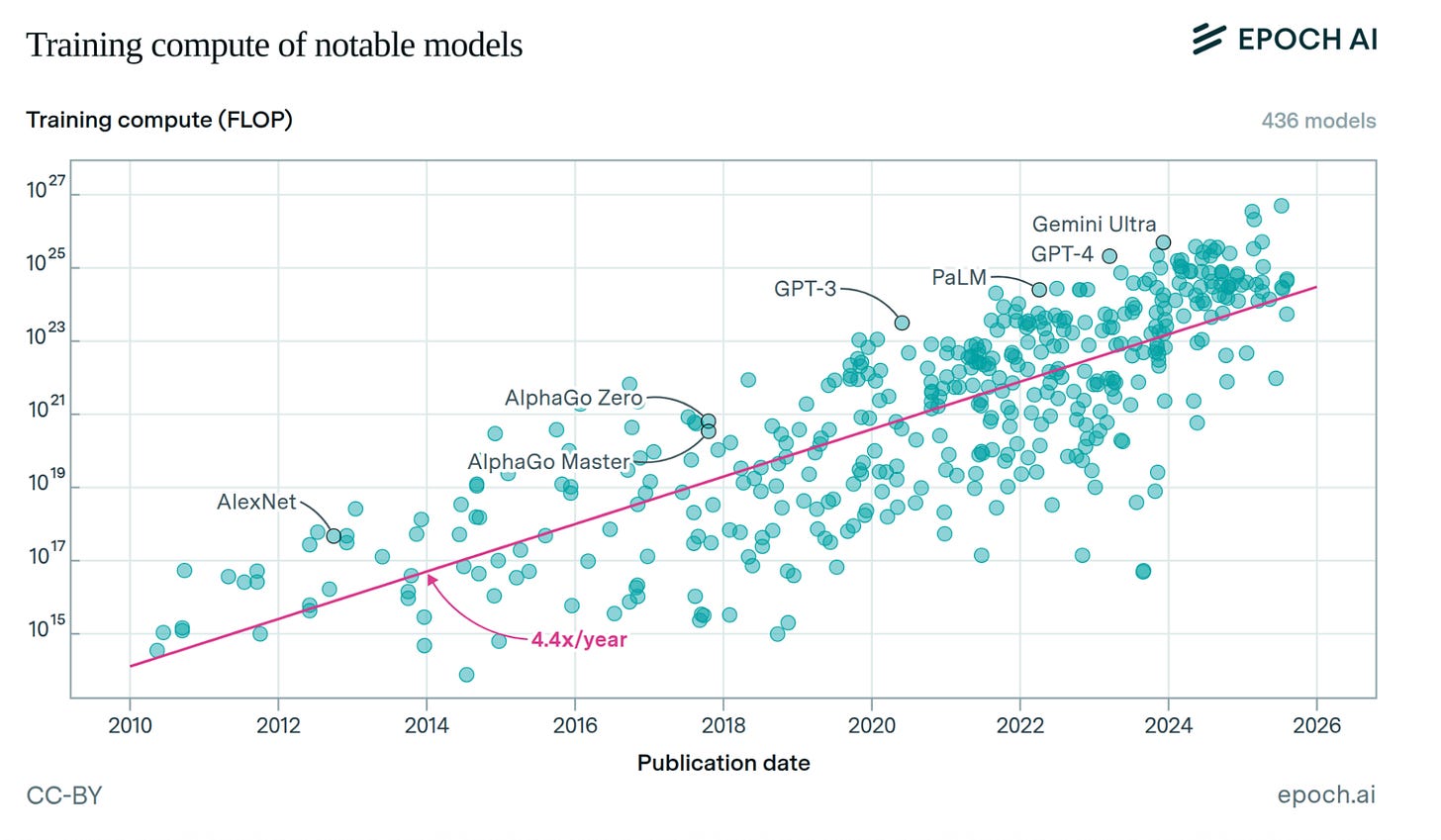

Countries face various technological uncertainties when deciding how ambitiously to build out their computing infrastructure, from the robustness of past hardware trends over the importance of low-latency inference to the compute demands of various sector-specific applications.

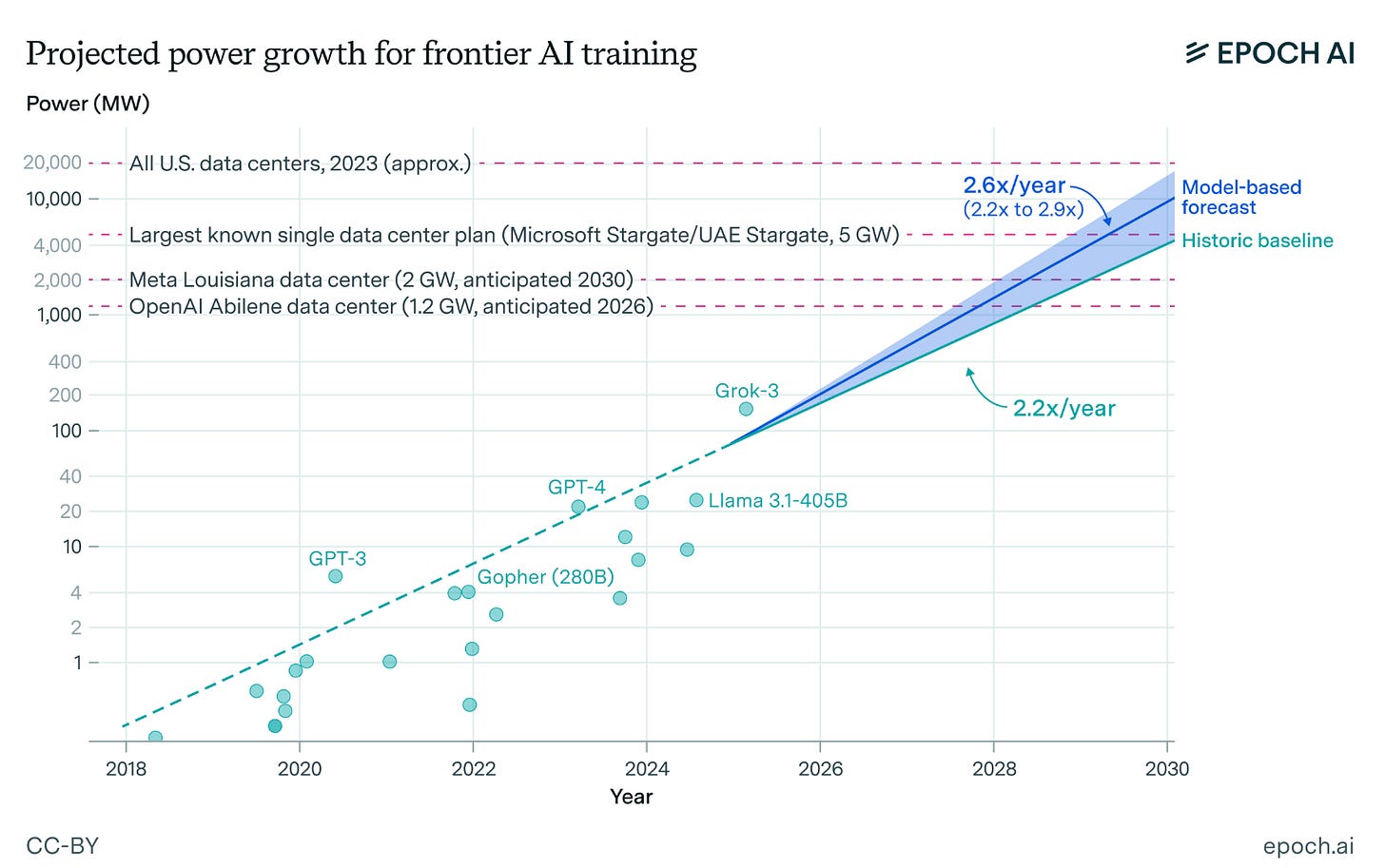

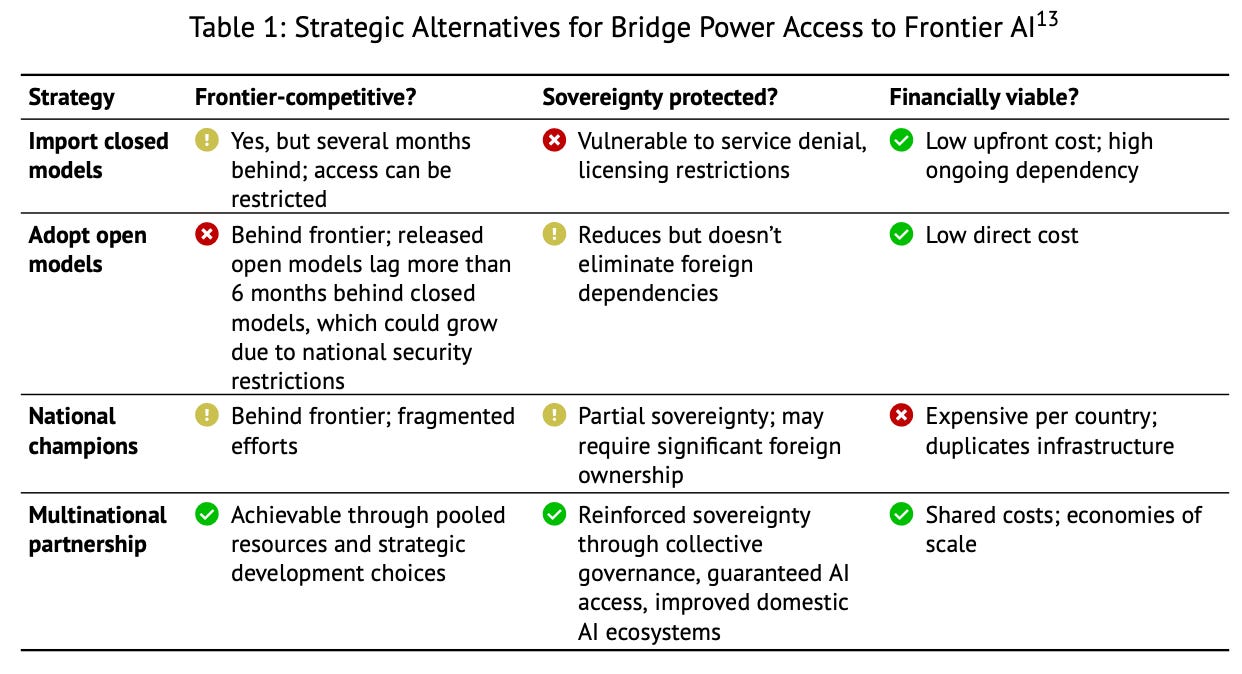

For middle powers, a distinctive set of strategic questions complicates things further. Unlike AI heavyweights like the US or China, they first need to decide whether they should try to compete at the frontier at all. If this is their path, they will need large training clusters and the corresponding energy infrastructure. If they focus on AI adoption instead, the focus shifts to smaller, decentralized clusters for inference and sector-specific training. This question isn’t academic, as it affects whether a country should spend $1B, $10B or north of $100B on AI infrastructure. Other tricky questions, discussed below, include: How much sovereignty can a country realistically achieve across the tech stack? Where do the GPUs come from? Should it join forces with other middle powers or just negotiate unilaterally with the US or China?

Methodologically, a country can approach the question of how much compute it wants to have on its soil in two different ways:

Top-down, supply-driven approach:

Estimate the global supply of H100-equivalents1 at a given time in the future (based on trends in chip efficiency and production).

Decide which share of the global supply a country wants to have on its own soil (e.g. by anchoring on its nominal share of global GDP).

Bottom-up, demand-driven approach:

Use historical data and economic modelling to estimate demand growth for training and inference in different sectors.

Aggregate over the whole economy/public sector to calculate national compute demand.

Decide which share of the national compute demand a country wants to cover through data centers on its own soil.

The two approaches view compute through different lenses. The top-down approach treats compute as a strategic resource with high option value, similar to energy or human talent. On this perspective, as a rule of thumb, countries should try to have more of it, at least in proportion to their desired level of economic and political power.

The bottom-up approach – which we follow in the report – treats compute as an infrastructure good like railways or ports. On this perspective, compute also has lots of strategic significance: It is broadly useful for a wide range of purposes and at the foundation of a country’s future competitiveness and sovereignty. However, it is also expensive and takes many years to build. Therefore, compute targets should be based on demand models anchored in economic reality. In our study, it yields more conservative estimates: between 850k and 3,4m H100-equivalents for adoption-focused strategies, compared to 9,5m under the top-down approach.

2) However, there’s no timing trap and the risk of overbuilding is overstated.

Both top-down and bottom-up approaches can only reduce uncertainty so much. Does this lead to a ‘timing trap’, where middle powers need more information before embarking on ambitious buildouts, but waiting for this information comes at the risk of falling even further behind? I think this trap can be avoided: It’s actually not that difficult for middle powers to strike the right balance between underbuilding (thus risking dependence and economic shocks) and overbuilding (thus risking stranded assets).

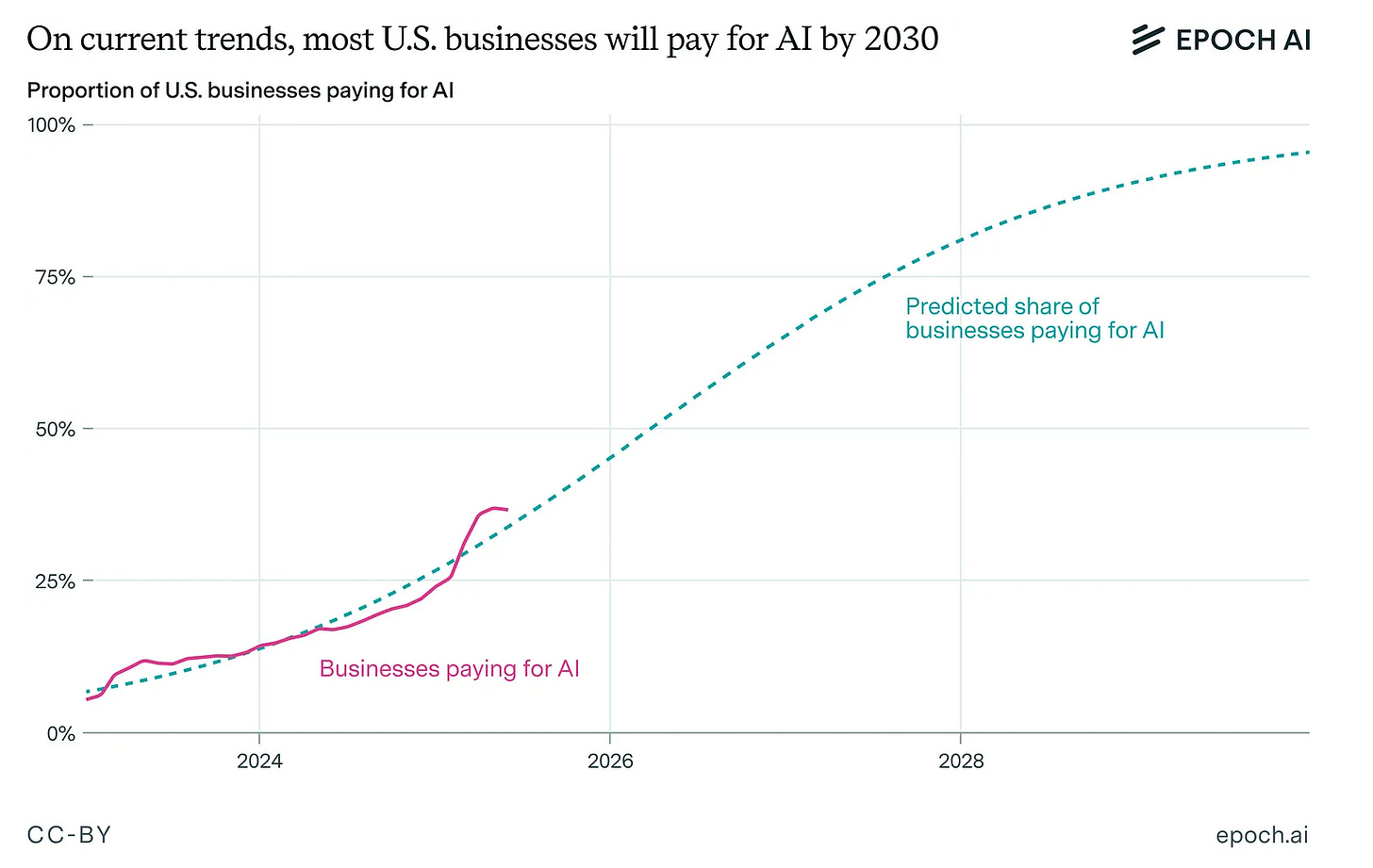

Even by conservative estimates, inference demand in countries like Germany or the UK will grow rapidly in the next few years. This is the result of recent economic modeling by McKinsey and Deloitte, who are probably less bullish on near-term AGI or labor automation than many people in Silicon Valley, DC or Beijing. Right now, middle power capacity is far below even those conservative estimates.

For example, if all currently announced plans materialized, Germany would increase its compute stock to ~200k H100-equivalents. Even if you add compute from new hyperscaler data centers that are notoriously hard to track, and leave a high margin of error, this is very far from the total inference demand of 4,3m H100-equivalents that our study estimates for Germany in late 2028. Of course, foreign cloud providers will service some, perhaps even the majority, of this demand. But for a variety of reasons – including data sovereignty, latency, ecosystem effects and geopolitical hardening – Germany will also want some data centers on its own soil. It could build a lot of them before even coming close to exceeding projected demand.

3) Full-blown AI sovereignty is a myth, but counting on foreign cloud providers could still prove fatal.

“AI sovereignty” can mean anything from the origin of a country’s widely used models, the GPUs on which they are run, the physical location of the data centers in which these GPUs are placed, or some combination of these and other factors. For the time being, full sovereignty across all these dimensions isn’t realistic for any middle power (nor is it necessarily desirable, as exaggerated sovereignty ambitions blend into isolationism). This is clearest in the case of advanced AI chips, which even the EU together isn’t remotely able to produce and must instead import from the US.2

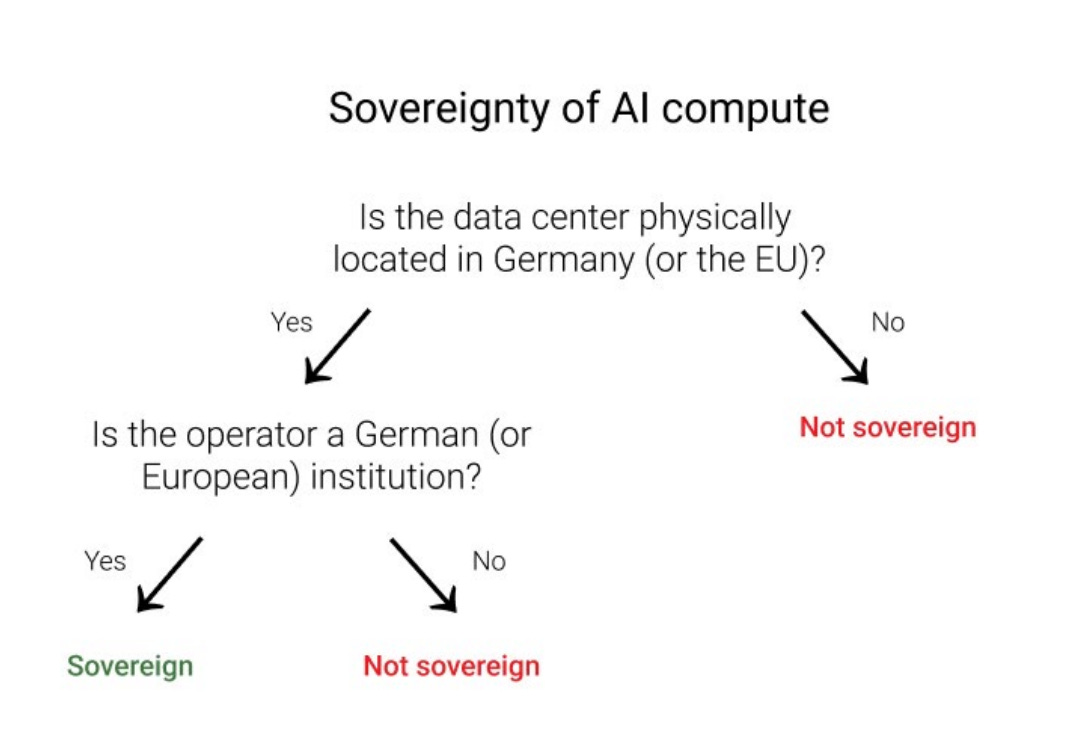

Sovereignty definitions that insist on a domestic hardware stack are therefore not very actionable for middle powers. In our report, we instead propose a definition that focuses on two other, more directly policy-relevant conditions for a data center to be sovereign: 1) being physically located in your country and 2) being operated by a domestic company.

One could push back against this and say that, as long as the GPUs come from abroad, this is not real sovereignty. But I believe that the above conditions make a big difference: If your compute is controlled by foreign cloud providers or data center operators, they can physically cut your access at any time. Even if they had economic or legal reasons not to, the threat potential alone worsens your bargaining position. If, however, you import GPUs for domestically operated data centers, you are free to use them as you see fit.3 Foreign governments could still threaten to cut off future chip exports. But that’s very different from an instant off-switch for critical digital infrastructure – even if triggering it would only be on the table in a situation of extreme geopolitical tension. You would still have a few years of runway until your existing GPUs need to be replaced or become outdated. You can use that time to think about a solution, which improves your bargaining position.

Apart from such adversarial scenarios, middle powers have further reasons to invest in sovereign compute. Today, the market for cloud compute is mainly split between the US and China. But it’s far from clear how long US cloud providers can serve the whole world with AI compute – or at least, the majority of middle powers for whom the Chinese cloud is not an option. Even the US can only build data centers so fast and is bottlenecked by problems familiar to middle powers, such as slow permitting or congested grids. This limits how much compute it could possibly export to other countries. And every US admin will, to a greater or lesser degree, prioritize the AI needs of its own economy, public services and military before it shares its compute with the world. Counting on a future where the US has enough spare capacity to enable similar levels of AI adoption (and thus competitiveness) in other countries is a risky bet for middle powers. The US might repurpose their cloud compute at any time; sovereign data centers on domestic soil are middle powers’ hedge against this.

4) Middle powers need a more active stance towards the US export regime for AI chips.

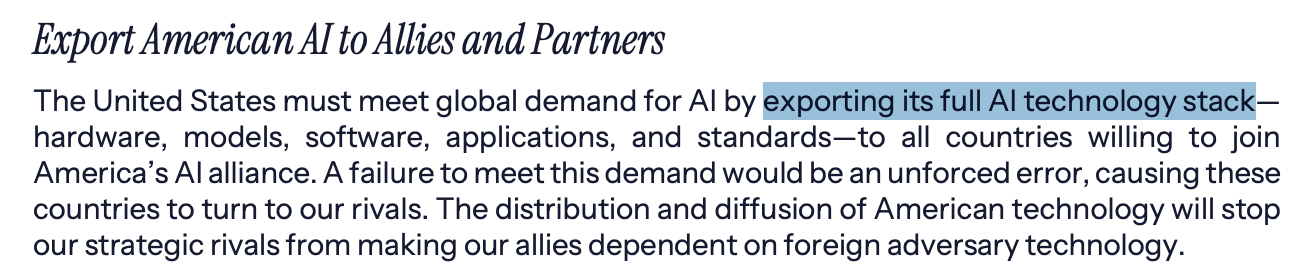

Can middle powers buy enough GPUs for their own data centers? This could be more difficult than leaders in Paris, Brussels or Berlin expect. The US government might use its GPUs as strategic leverage and export them only under strict conditions – e.g. for use in data centers operated by US companies, as the AI Action Plan envisions. Or it might curb chip exports because domestic training and inference demand grows very fast and the US decides that it needs its GPUs for itself (think of an expanded version of the GAIN Act). This would immediately kill sovereign AI initiatives, such as the EU’s AI Gigafactories.

My impression is that many middle power governments should confront this challenge much more actively and engage in trade diplomacy to secure GPU access in the future. As others have written about, this requires them to think about which of their existing strengths and comparative advantages they can leverage for privileged GPU access. They could also pool their efforts: For example, European leadership in EUV lithography (ASML) and its inputs (e.g. masks from Zeiss, lasers from Trumpf, photomask writers from IMS Nanofabrication), combined with South Korean leadership in HBM (SK Hynix, Samsung), could together be translated into substantial bargaining power..

5) Energy constraints raise difficult trade-offs and could force new alliances.

Data centers are an energy-intensive business. Electricity generation and grid expansion are a major bottleneck anywhere in the world (though least of all in China), but the problem is especially acute in Western middle powers with slow-moving bureaucracies and an unfavorable geography. Germany is a prime example: Permitting can take two years or more, grid connection 5-7 years, energy prices are high, and Germany doesn’t have France’s reliable nuclear power or Norway’s abundant hydropower.

There are still several things that a country like Germany could do. In the short term: combine solar and wind power with advanced battery technology to power data centers 24/7, or expand HVDC transmission systems to bring offshore wind power inland (such as in South Korea). In the longer term: make progress on Enhanced Geothermal Systems, or be the first country to achieve engineering breakeven for fusion energy and build the first commercial reactors (though, just as with AI, the US and China are in the lead right now).

The question is whether this could work quickly enough to unlock enough energy – in particular, without relying primarily on natural gas. Those who are pessimistic about this will increasingly look to regional coalitions. Especially for frontier training, a European consortium – potentially with other middle powers like Canada or Japan – could instead pool its resources and relative strengths. For example, it could use abundant green hydropower from Norway to power a large training cluster, throw in R&D expertise and industrial data from France, Germany and Italy, build highly secure evaluation and testing facilities in Switzerland – and aim for a third pole in the global AI landscape besides the US and China.

Regional coalitions multiply options and look more sustainable, economically and ecologically. But trade-offs exist with sovereignty and speed: A country might be unwilling to share its sensitive data even with allies. A large and ambitious infrastructure project across several countries, let alone the entire EU with its notorious bureaucracy, could be too slow to be competitive. Especially for more powerful players like France and Germany, a small coalition of the willing that gradually grows over time could be more promising.

6) Compute doesn’t solve all problems, but middle powers must break out of a vicious circle.

Compute is only one factor in the AI triad, and doesn’t get you very far without enough data and efficient algorithms (which in turn depend on human research talent – at least for the time being). Favorable regulatory conditions and enough capital to afford compute, data and algorithmic innovation are similarly crucial.

Therefore, data center investments will only pay off if middle powers support their AI ecosystem as a whole. Promising measures include unlocking venture capital (e.g. by allowing pension funds and insurance companies to invest in high-risk, high-return AI companies), simplified visa programs for international top talent, pragmatic copyright and data protection rules that don’t make AI training overly burdensome, boosting economy-wide AI adoption (e.g. through special depreciation of AI investments), and facilitating the transfer between foundational research and commercial applications.

Critics of ambitious compute buildouts are hence right to point out that merely building lots of data centers – let alone making flashy announcements without the political will to follow through on them – doesn’t make anyone competitive in AI. Yet this does not support an argument frequently made in this context: that investing billions in AI infrastructure is irrational for any country without frontier AI companies willing to train on them. One reason is that even without such companies, middle powers may still want to enable localized, low-latency inference through data centers on its soil – especially when AI is heavily integrated into industrial applications. Moreover, for applications in sensitive areas, such as national security, healthcare or critical infrastructure, there’s a need for sovereign data centers that meet the highest standards of information integrity.

Here, I want to focus on a different point: Middle powers lack competitive AI companies precisely because access to compute, capital, data and talent is so limited. That’s why, if you’re an excellent ML researcher from Germany or France or India and have a great idea for an AI company, your default is to go to the US. Middle powers thus find themselves in a vicious circle: weak infrastructure and unfavorable conditions lead to a lack of national AI champions, which in turn leads to a political deprioritization of AI and raises skepticism about the need for AI infrastructure. The only way out of this vicious circle is to boost your AI ecosystem across all layers. Compute isn’t everything, but that’s not a reason against building data centers – it’s a reason for doing that, together with a bunch of other things.

7) Middle powers can step up their game only if situational awareness and political prioritization increase.

AI sovereignty has become a ubiquitous theme in political discourse, but there’s too little awareness in middle powers about what this requires in practice. For example, the EU’s AI Continent Action Plan aims for “EU leadership in frontier AI”, and the recent Apply AI Strategy doubles down on using the planned 5 Gigafactories for this purpose. The problem is that Gigafactories are unlikely to sustain frontier training by the time they become operational. Similarly, it’s good that OpenAI and SAP will make leading US models available to the German public sector, but policymakers should mind the gap between the promised 4.000 GPUs and the hundreds of thousands (or even millions) of GPUs likely required to meet future inference demand in a country like Germany.

While situational awareness is important for setting realistic goals, a healthy amount of centralization makes it easier to execute them quickly and with priority. Right now, AI infrastructure is too often handled by different ministries and sub-departments, without central coordination across relevant areas, from energy over permitting to financing, hardware access, and information security. Even in the UK, arguably the middle power that takes AI most seriously, attempts to boost data center buildout through “AI Growth Zones” are slowed down by bureaucracy. It often takes a crisis for middle powers to show that ambitious infrastructure projects are feasible within short timeframes if the political will is there (think of how Germany built LNG terminals within months during the 2022 energy crisis, with strong leadership through the Federal Chancellery). My hope is that governments take the geostrategic significance of AI seriously enough to act decisively before a crisis hits.

Bottom line

Currently, the US and China are leading in AI. Middle powers could catch up if they really want to, especially when pooling their resources. The amount of investment and political will required is enormous, but so are the stakes.

H100-equivalents are a standard metric to compare computing power across different chip types or data centers. To convert into H100-equivalents, you divide the performance of a chip in the lowest supported precision (among 32-, 16-, or 8-bit) by the performance of an Nvidia H100 GPU in 8-bit precision. See Pilz et al. 2025.

Chinese chips are not a viable alternative for most middle powers, for a mix of geopolitical reasons and supply chain constraints on the Chinese side.

This might change at some point in the future, if GPUs were shipped with hardware-enabled mechanisms that allow for remote verification, control and shutdown.