Making AI Progress More Legible

AI progress has been rapid throughout 2025, but it’s still easy to miss. One challenge for AI governance in 2026 will be to make it more visible to policymakers and the public.

Visiting my family over Christmas, I was amazed by the level of everyday technological penetration, especially among my older relatives. They give intricate instructions to their Alexas, track steps with a smart watch, and make TV screens appear out of nowhere at the press of a button. When I look at this, I almost feel like an old man. In private, and bracketing AI for a moment, my technology use consists mostly in listening to music on my laptop speakers and sending the occasional text message to a friend.

Yet in the grand scheme of things, it doesn’t feel like any of these smart devices really matter. They are pure gadgets. Like microwaves, they do change people’s lives and will show up somewhere in future history books. But just like today’s historians don’t look back at the “microwave age”, future historians won’t consider the “smartphone age” or “Alexa revolution” as important reference points. These inventions are too small for that – they don’t cause structural shifts in how power is distributed across society, they don’t upend major economic equilibria, and nations don’t fight wars over them.

So why is it that, as 2026 begins, the technologies that most seem to occupy people’s daily minds are smart speakers and iPhones, rather than AI? To be clear, AI is getting major attention since OpenAI released ChatGPT in 2022, and I assume its implications came up at many dinner tables at least once over the past holidays. But news reporting on AI is often shallow and very few people really appreciate the size of the challenges that are coming at us with high speed. Why is that and what we do about it?

Progress in 2025: Invisibly on Trend

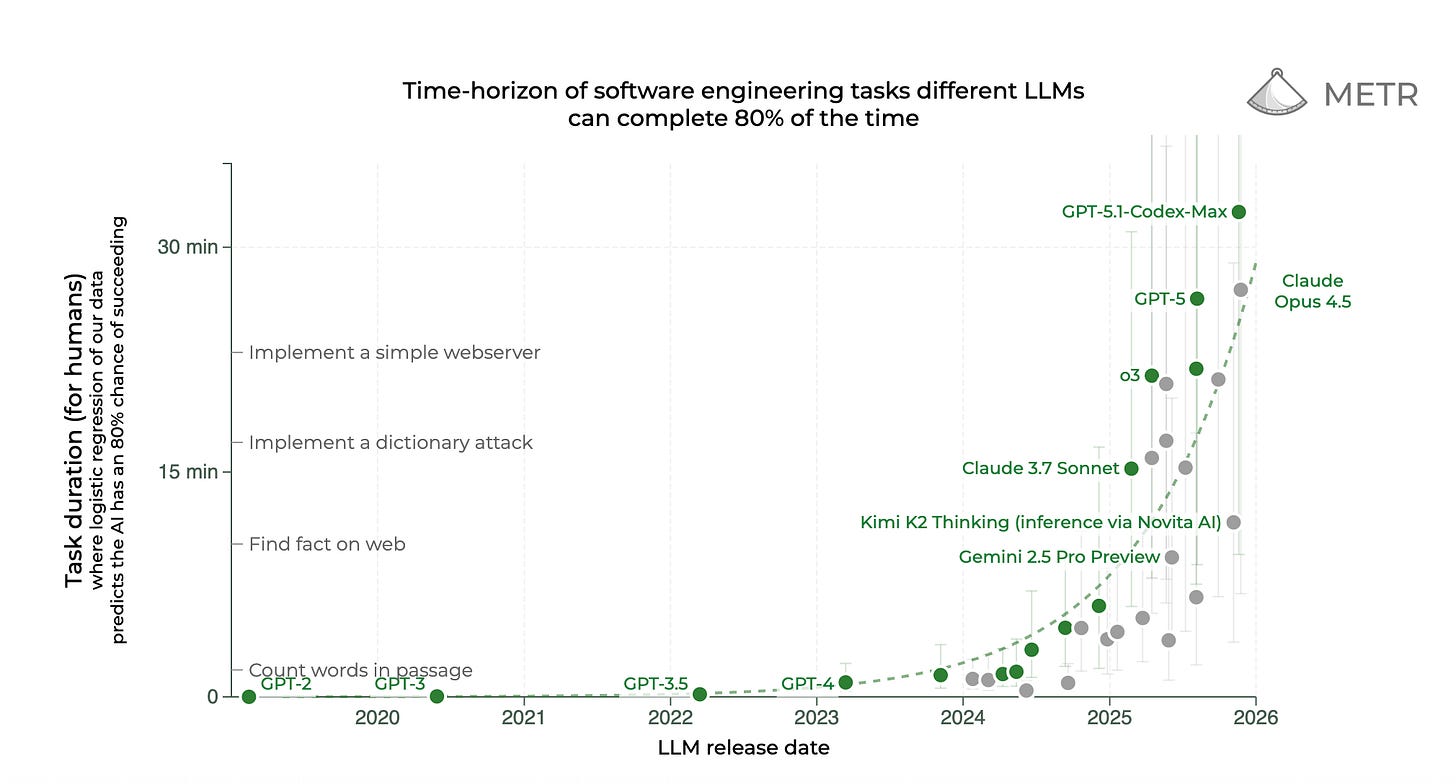

In 2025, AI progress continued to be very rapid. Benchmark performance followed exponential trendlines, most notably in the METR study on task horizons. Real-world impact, however, mostly materialized in coding agents, maths olympiads and arcane corners of modern science – and so was largely hidden in sight. At least for now, this has nothing to do with important information being classified, as some people feared in 2024 when AI discourse became increasingly securitized. In fact, the knowledge is basically out there if you read the right Substacks, or as Jack Clark put it: “[I]f you have a bit of intellectual curiosity and some time, you can very quickly shock yourself with how amazingly capable modern AI systems are.”

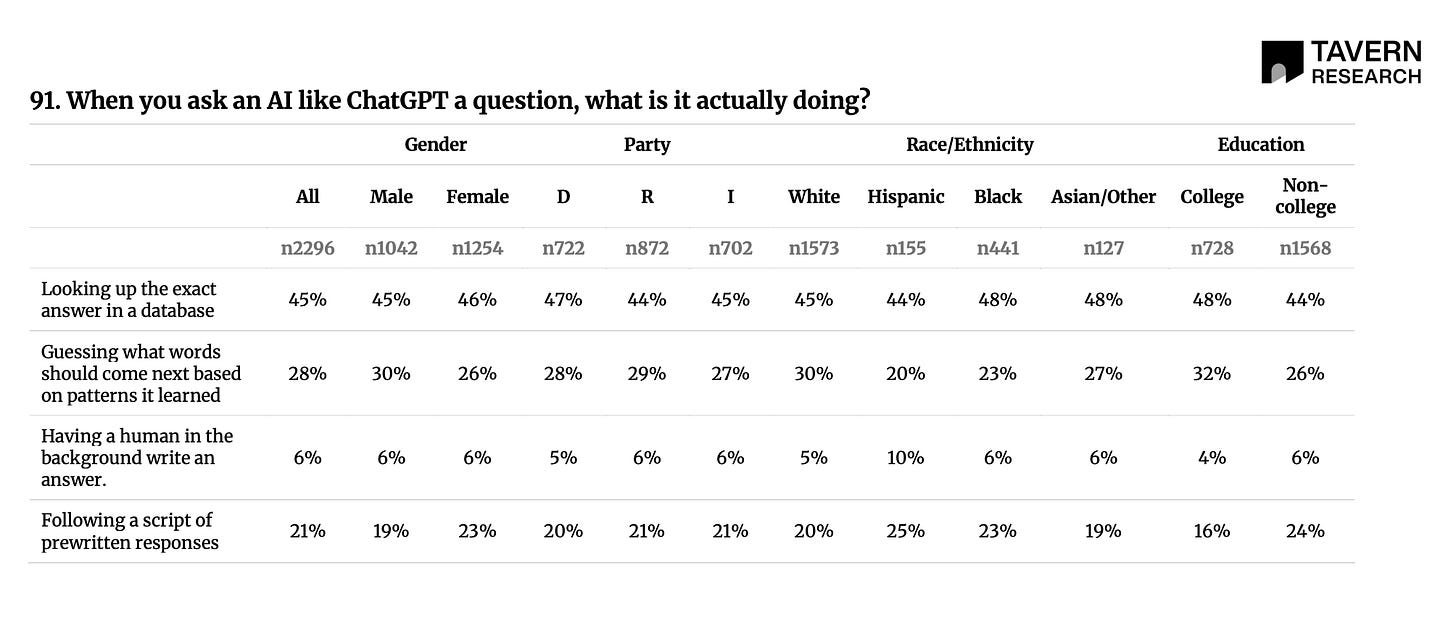

But most people, including mainstream journalists, typically have better things to do than reading those Substacks, and so for them, AI progress remains quite illegible. This is partly because recent AI progress is, indeed, fairly ephemeral. As Clark says: “I walk around the town in which I live and there aren’t drones in the sky or self-driving cars or sidewalk robots or anything like that.” So far, progress in general-purpose AI is mostly a software revolution, which is inherently harder to grasp than a home robot. For example, respondents in a recent survey said that when you ask an LLM a question, it looks up the exact answer in a database (45%), follows a set of prewritten responses (21%) or a human in the background is writing the answer (6%). At least according to this survey, it’s not clear to most of the public that modern AI models are doing something much more impressive than that (even if it’s hard to say how the models are doing it).

2026: Same Procedure as Last Year?

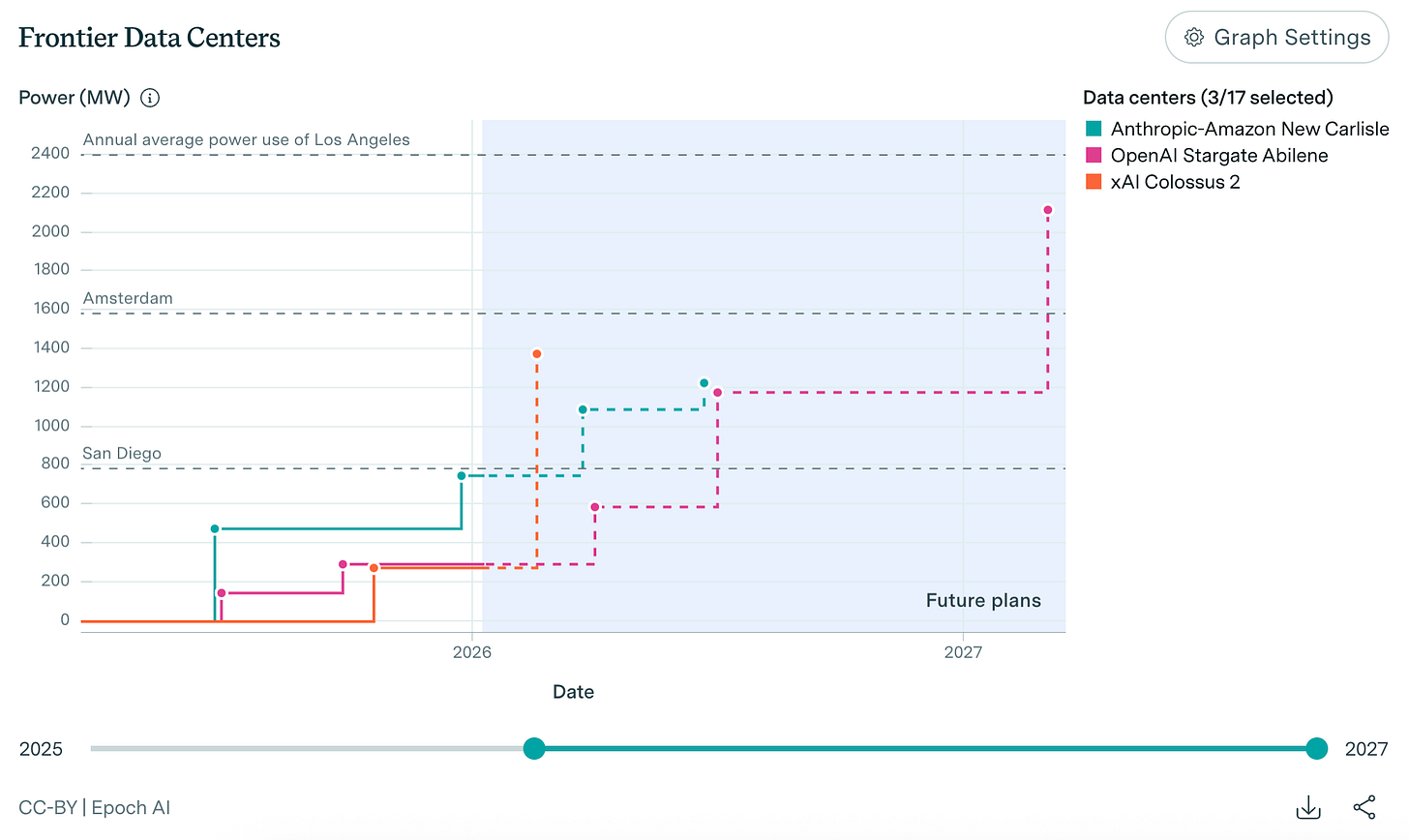

Many experts expect further capability jumps in 2026: The first 1 GW clusters are expected to become operational and allow unprecedented model scale-ups, Anthropic insiders think they will crack some form of continual learning, and OpenAI allegedly found a way to get even more value out of synthetic data. Further progress, perhaps at an even greater pace, could come from closing (or at least narrowing) RSI loops beyond data, e.g. for algorithms or compute.1 Some will think that’s mostly industry hype. But often the same people thought this already at the start of 2025, which turned out not to be a year of stalled progress.

Even if progress remains rapid in 2026, however, I wouldn’t be surprised if legibility remains low. AI companies will continue to boost capabilities in domains that don’t directly affect the average user, such as AI R&D automation. Low legibility also holds for many enterprise use cases: a lot of money could be made here, but progress will only be visible to domain experts at first – at least until AI automation makes a clear, sizable impact on labor statistics. While it’s hard to rule out, it doesn’t look to me like this will be happening as early as 2026. For example, coding agents like Claude Code hold enormous potential for automating knowledge work, but their widespread use is bottlenecked by organizational inertia and lack of imagination by the average user – factors that are harder to smooth out than UI issues.

More generally, I think it’s about as likely as not that when AGI arrives, there won’t be a consensus over that fact. This puts pressure on any policy strategy on which its arrival is a singular, verifiable event that can be publicly announced to trigger the necessary conversations among decision-makers and society. Instead, people must be looped in from the start and kept informed throughout the current transition. Initiatives like the International AI Safety Report – whose next iteration my co-authors and I are going to publish in February – provide a continuous monitoring of capability trends and societal risks, but can only be a first step.

How Could We Make AI Progress More Legible?

Over 3 years after the ChatGPT release, the world needs another push to make AI progress more visible. I’ll end with a few quick ideas:

If you’re in AI governance:

Connect future trends and potential threat models with detailed accounts of how AI is already transforming various industries and scientific practice today.

Use interactive demos and tabletop exercises, which can be more helpful than just memos, papers and op-eds.

Spend more effort on high-quality video content with a wide target audience, and less on blog posts on arcane Substacks (like this one).

Become really good at explaining stuff: learn how to craft helpful analogies and intuitive visualizations.

Understand AI literacy and upskilling as an ongoing challenge, rather than ad hoc initiatives in response to major events every few years.

If you’re in industry or technical research:

We need more benchmarks like GDPval or Remote Labor Index that track capabilities on real-world tasks. They complement benchmarks like GPQA Diamond, ARC-AGI or RE-Bench, which are crucial measures of raw intelligence and AI R&D automation, but don’t always map neatly onto real-world impact.

A greater focus on robotics, autonomous vehicles (lest we hamstring them through excessive regulation) and AI-powered devices that truly increase productivity could be the next big moment for public AI awareness. If you have a robot clean your bedroom, the question whether it is acting autonomously or being remote-controlled by some human in the background becomes much more acute compared to the average ChatGPT prompt.

Bottom line

Until now, AI progress has mostly materialized in areas with low public visibility, like benchmarks and coding workflows. Instead of waiting for the singular reveal, the AI community seems well-advised to increase AI’s salience through tangible demonstrations and continuous upskilling. The alternative is a society that sleepwalks into deep structural upheaval.

Think of AI systems improving the algorithms of their successors, or the efficiency of the chips on which they are trained – leading to “recursive self-improvement” (RSI).